Make America's trade policy toward China sustainable

- By Zhang Lijuan

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, August 9, 2016

E-mail China.org.cn, August 9, 2016

|

|

|

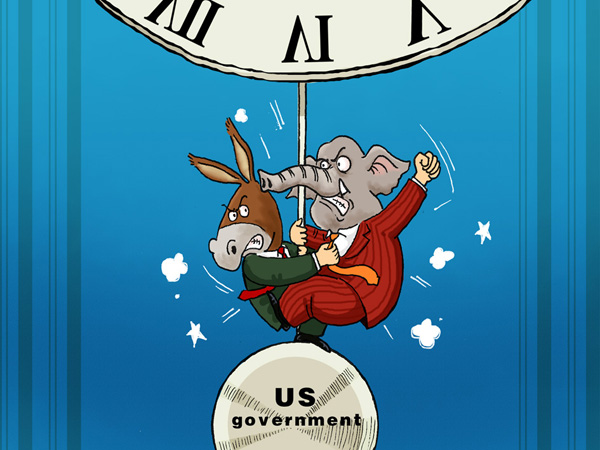

No time to fight [By Zhai Haijun/China.org.cn] |

The current presidential campaign in the United States has featured more unique aspects than any previous campaign in recent history. But one aspect is all too familiar, an untiring advocacy for tougher trade policies with respect to China.

Trade economists in the United States are very used to this political ideology. For decades, presidential candidates have enjoyed using sharp attacks on China to gain public attention and to grab votes. As George Washington University professor Robert Sutter has described, "the president-elect, and U.S. politicians in the following years, found that criticizing China and U.S. policy toward China provided a convenient means to pursue political ends."

However, another consensus is that right after the presidents take the oath of office, they tend to develop friendlier, non-hostile and bilateral trade relations with China. This is true for both past and present administrations.

Academies in China and the United States, in general, recognize that the United States and China are deeply interdependent and interconnected with each other in today's global trade and economy. A sustainable U.S.-China bilateral trade relationship also serves to better the global economy.

Inside the United States, the most frequent arguments for a tougher trade policy toward China include the long-lasting U.S. trade deficit with China and jobs exported to China by offshoring and/or outsourcing. These arguments become less convincing today than during the days when trade in goods represented the major form of global trade and Global Value Chains (GVCs) had not burst onto the trade policy scene. With the multitude of complicated global supply chains taking the lead, it is no secret that more than half of China's exports to the U.S. displace exports from other nations rather than American products.

Job protection has always been a major political bargaining issue when making U.S. trade policy. The loss of manufacturing jobs in the United States continues to serve as the politicians' top argument for evoking trade protection measures against China. The fact is, due to today's interdependent trade structure and interconnected GVCs, politicalized trade policy against China will produce negative effects with respect to American interests.

There is no doubt that China is a vital player in today's Global Value Chains. Many such chains cast the U.S. and China in mutually irreplaceable roles. China's labor advantages will continue to drive its manufacturing competence, while the U.S. will continue to exploit its technological innovation as an advantage. In fact, almost every imported item labeled "Made in China" has some sort of value added derivative from the United States. The solar panel case against China has proven to be a good example of how special tariffs on Chinese imports will negatively impact other interests in the American solar industry; for example, solar cell producers ship off cells to China as part of the supply chain. If local services are counted, the overall employment level in the American solar industry is far larger than employment in the solar panel manufacturing sector. In the words of Paul Krugman, in considering the effect on overall employment, "trade deficits meant two million fewer manufacturing jobs and two million more [jobs] in the service sector."

Besides, today's manufacturing industries are more technology-driven than ever before. While traditional low-paying manufacturing jobs are in diminishing, employment opportunities in industries related to robotics and digital technology are booming. Today, "smart manufacturing" is the cornerstone of the American economy, thus ensuring that the manufacturing sector will continue to have a critical role in creating jobs. It is the technology innovation that will drive the future of manufacturing.

In addition, China's legacy of cheap labor is changing as well. Labor costs in China are much higher today than they were a decade or even two to three years ago. As traditional manufacturing jobs have been shipped overseas and perhaps will never return to America, tougher trade policies against China will offer little help in terms of job creation in the U.S., and they will contribute little to balance the U.S. trade in goods with China.

In academic society, the American economists have never stopped debating the evidence regarding China's role in U.S. job losses. In reality, American politicians have never stopped using the China factor as a means to fight for election votes, but this kind of strategy could easily result in diminished public interest and may go so far as to hurt consumer interests. It is true that the American trade policy possesses super power connotations in the world, but it is also true that today's world, efficient trade policy, in the face of globalization 2.0 and WTO 2.0, requires strategic cooperation rather than confrontation in solving problems related to sustainable trade development. Job creation now challenges every nation. If the United States and China can work together to address such challenges, they will send a strong and positive signal to the global community and to those advocating for economic sustainability.

Until now, China and the United States do not have bilateral free trade or investment agreements. But, to date, that has not stopped China from becoming the number one trading partner of the United States in terms of trade in goods. Therefore, to help with U.S. job creation, a sustainable trade policy toward China is necessary. Any seasonal trade policy will result in severe consequences against American interests. What really matters to both sides is a responsible trade policy -- an approach where trade policy is not a popular political tool but a strategic instrument to serve bilateral economic welfare and to support multilateral trade governance.

Zhang Lijuan is a professor with Shandong University, China. She is also a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:

http://m.91dzs.com/opinion/zhanglijuan.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.