China's education system impacts how people act

- By Ember Swift

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, October 28, 2012

E-mail China.org.cn, October 28, 2012

The negative effects of an exam-based education system are evident in everyday life in China. An educational system that requires students to memorize, regurgitate information and follow instruction to please teachers is not without drawbacks. The long-term effects of never questioning authority and cramming for tests have created a society absent of free thought.

|

|

|

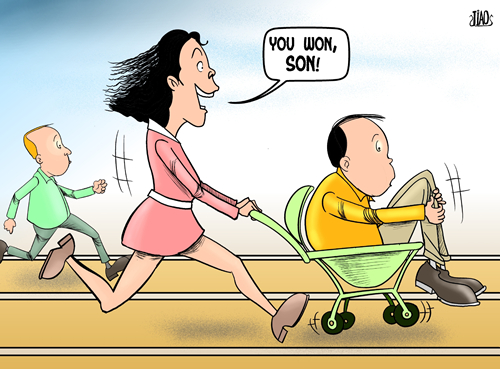

Mother's competitive advantage [By Jiao Haiyang/China.org.cn] |

A recent article from the New York Times online blog, Latitude, explains that China's 10-year plan for education reform introduced in 2010 acknowledges the above problems, and highlights the obstacles implementing education reform. These include weakening the socialist paradigm in which education is a means to produce workers, and the fear that a more individual-based education system will undermine social control. An obstacle Eric Abrahamsen failed to note, however, is the general unwillingness of the Chinese public to associate their outdated educational system with interpersonal conflict.

For example, my Chinese mother-in-law wanted to teach me how to cook Chinese food. In her experience, her role as the teacher is to bark instructions while a student's role is to listen and watch. I was expected to memorize what I saw and heard, and then be able to reproduce it. Our first lesson was how to make 菜餅(spinach pancake). When I tried to replicate my mother-in-law's deft cooking skills without her guidance, I was chastised for not having been a good enough student.

Coming from the West, I grew up "learning by doing," by being asked to think through a new task and solve problems as I go. Failures are not criticized in the West; the attempt is celebrated as a learning stage. Western adolescents are also asked to share their opinions freely. Chinese students aren't so lucky.

I recently accompanied a friend to a store in Beijing to return a food item that, when opened, was already stale. The expiration date suggested that the product should still have been fresh, but for some reason the food had already gone bad.

The store clerk was adamant that she could not refund or exchange the purchase because the date was not yet past due. These were "the rules" and she had been taught to follow them without question. She did not have a personal opinion in the situation. The manager, when called, also quoted from the same rule book.

My friend's Chinese was faltering as she got flustered, so I quickly suggested that we all "taste test" the product to prove it was inedible. The suggestion was audacious enough to bring the situation out of the confines of a dusty rule book and into the specifics of human reality. The manager reluctantly relented and agreed to exchange the item.

The manager ended the conversation by giving us a strict warning that this would not be allowed to happen again, and my friend believed that the store would begin taking better care of its products. However, the manager actually meant that in future, my friend would not be able to exchange products that weren't past due, even in a similar situation!

Their differing interpretations of what the manager meant can be traced back to how they were educated.

While the end goal should always be customer satisfaction and problem resolution, service providers in China often blindly follow rules or regulations without questioning their logic, even in unique circumstances. Employees have been taught since grade school to never challenge authority. Situations such as overcrowding during the 2012 October holidays with 2000 stranded tourists on the top of Huashan Mountain exemplify this problem on a much larger scale. Unusual situations require novel solutions. But who will be brave enough to implement them?

I spent a short stint teaching an English writing course a few years ago, and experienced first-hand the effects of this outdated educational system on the minds of Chinese youth. Having asked my students to prepare one-page responses to various questions I asked at the end of each class, I began to notice a pattern emerge where most students would first research the Canadian perspective on these topics before writing a response. They wished, first and foremost, to please their Canadian teacher with the content of their answers rather than share their genuine beliefs.

Despite encouraging them to be free in their responses, reminding them that I was grading their English and not their opinions, little changed. As Eric Abrahamsen wrote in his New York Times blog piece, "Individuality [in Chinese students] suffers from a young age: by the time a student is entering college, much of the damage has been done." In other words, there was not much a short-term teacher from Canada could do.

China's education system will not change overnight, but acknowledging its wider impact is essential as educators and parents advocate for less rigidity and more educational alternatives for the next generation.

So, conceding that my mother-in-law is a product of a larger, flawed system, I can now forgive her teaching methods as I persevere in my quest to make a decent spinach pancake, but most students don't have this outside perspective.

At least, not yet.

The author is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit: http://m.91dzs.com/opinion/emberswift.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.