| Home | Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

| Part 5 |

| Adjust font size: |

The Bomi’s beauty is quiet and peaceful. Here it feels like being in a delightful paradise. But the appeal of the The road from To some people the The route from Pelung to Zachu runs parallel to the There are steep cliffs at each side of the That said, the views here are very beautiful indeed. The 1000-meter-deep canyon looks like something that has been split by a giant mountain-cleaving axe. It extends ever southwards, its awesome precipitous mountains covered by endless vegetation, the type of vegetation dependent upon on how high up the mountain it is growing. Shrubs and broad-leaved trees predominate at the bottom, and the mountainside are covered with conifer trees. The valley is full of great vitality and at the same time it has beautiful views of morning mist, like those often seen in mountainous areas of Jiangnan, south of the Mr. Chen Yuansheng told me in Crossing landslide areas is very dangerous. Between Pelung and Zachu there are several landslide spots and although each is only about 30 or 40 meters wide, crossing them makes one tremble. The danger lies in the fact that one side you have the roar and running billows of a torrential river, and on the other a sheer slope. Apart from a string of footprints, there is no path across at all. The Tiger’s Mouth (Laohuzhui) is a danger spot. The local Monpa people have dug out a meter-wide path here. This path also makes a sharp bend on the edge of the cliff. And it would be all too easy to fall over the cliff while walking on the path that perches on top of it. But precisely because the way is so risky to walk, the outside world has had little influence here and it has remained a magical place. Exploration should be undertaken with great care and safety ropes should be used when passing through these dangerous areas. Explorers, particularly those with heart conditions or fear of heights, should hold on to the safety rope tightly to avoid accidents. We crossed four chain bridges suspended on steel cables, the bridge decks formed of planks. The bridges had no protection railings apart from some wires on both side, tied to the cables. But the wires were so widely spaced they were useless in terms of providing protection. The plank decks of the new bridges were well made, while those of the old bridges has voids here and there. Walking across these bridges, travelers are often frightened by the roaring river below. Even so, one must take his time about it for fear of stepping into a gap and falling. As soon as one steps onto the bridge, it starts swinging left and right, and in this case one must immediately sit down or lie on one’s stomach so as to reduce the vacillation and stop oneself being thrown into the river. Three of the four suspension bridges are between 60 and 70 meters long, and the fourth is a massive 180 meters. Sometimes local people replace broken planks with new ones, often with the bark still on. The new planks are slippery and when walking on them, one must take care not to slip and fall. In fact, we were fortunate. In the past there were no suspension bridges across the For us, the most testing section between Pelung and Zachu was the tortuous path near to Zachu. Its elevation is between 600 and 700 meters. It was near noon when we climbed the path and was so hot we were soon sweating and gasping for air. Luckily the elevation was not very high and the plentiful vegetation there provided sufficient oxygen, otherwise some of us would have been worn out. Then we came to a hill covered with green wild plantains, which looked very charming under the snow-capped mountains. We were jubilant because we could see Zachu from there. At noon we saw a village with fields of rapeseed, fences and flocks of sheep. We finally reached Zachu, our destination point at the end of the The journey from Pelung to Zachu had taken us two days. On the first day, while choosing a campsite we found several hot springs. It was an unforgettable experience. In fact, there are many We left Pelung in the morning. After climbing over a mountain we continued walking until five in the afternoon. We were very tired and hoped to find somewhere to pitch camp. My teammates ahead saw a stretch of sandy beach left of the riverbed and we erected our tents there. Some teammates discovered a hot spring nearby, a discovery that delighted everyone; it meant we could relax in the spring after a hard day. I dashed off to check it out; there was a rock face three or four meters high with a large red stone in the same color as that of the stones on the beach; the water was emerging from a small cave below the cliff. There was a pool four or five square meters in area and half a meter deep and two of the team were already having a soak in it. The water running through the pool formed a stream, which flowed about five to six meters and rushed off south, finally, emptying into the Parlung Tsangpo River 200 or so meters away. I asked my teammates about the water temperature. They told me it was fine for bathing and urged me to join them. Though I had seen commercially-exploited Two more teammates followed me in and so as to make space for them I moved a little to the left. Suddenly I felt the water was a little cooler and the more I moved the lower the water temperature dropped. I realized there were two different springs, one warm and the other cold, with less than a meter between them. Their water mixed into a stream. I was afraid of catching cold from bathing in cold water, which at plateau level might well turn into pneumonia, so I shifted toward the entrance of the hot spring cave. A noxious smell from the cave assailed my nostrils, so, fearing it might be harmful to health, I hurriedly drew away from the cave. When my teammates enjoyed bathing in the hot spring, I noticed the color of cliffs on both sides of the hot spring cave was pink and that of the cobblestones at the bottom of the flowing stream yellow. When the water was stirred it became muddy. After a while the water was clear again. I thought of the red cobblestones on the beach in the lower reaches of the stream. The different colors aroused my interest. I wanted to know why the cobblestones were red. I put on my underwear and walked in the warm stream to its lower reaches. I noticed the stone on the bottom of the stream and on the banks was seriously eroded. There was a stone in the midst of the stream. It was about As to why there were red stone in and around the spring, I think this was caused by microelements. At the same time I saw lines made by erosion on the middle and upper parts of the stones half-meter above water. I realized at last that the patterns of turtleback and the lines in various colors were made by erosion and that the lines on the stone high above waterline were made by overflowing water from the stream thousands of years ago. Soon afterwards, we found a larger hot spring not far from there. This spring was a little different from the one in which we bathed. The flow of the first one was gentle, while the second one spurted water into the air and thus had a water drop of less than one meter. Because of the drop, water flew down our hands when we bent over to get it. Besides, this spring’s temperature was about 50 degrees centigrade, a little higher than that one. The sandy beach campsite was beautiful. There were mountains, springs, white sandy beach, and lush and green forests. Besides, on the other side of the river was a waterfall dozens of meters high falling from the cliff. It was unexpected that all beautiful scenes gathered together before our eyes. The site was between Pelung and Zachu. When more people are attracted toward the Big Bend of the Grand Canyon of the There are four According to experts, when subterranean water infiltrates the depth of earth crust, it goes upwards because of rising temperature and becomes a fluid in which hot water and steam as main contents mixed with magma. The fluid goes through the chinks in crust to earth-ground. The heat goes out by two ways: geysers and hot-water explosion. The geysers are The

Crossing a steel rope suspension bridge

Crossing the river on a ropeway

Fording a stream

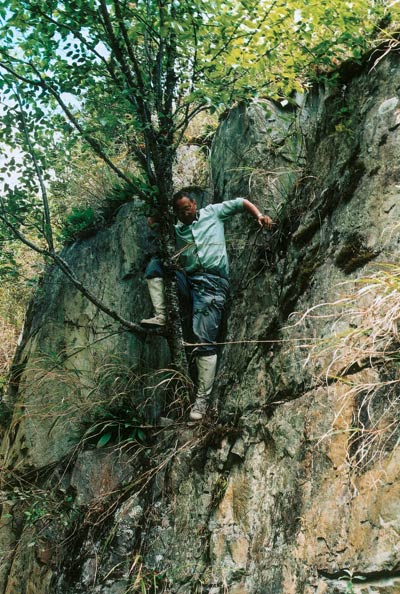

Surveying the cliff |

| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

|

| Related Stories |